Several years ago, Charlotte and I created some Nike ads that struck a nerve with a lot of people. Female people. Male people. Children as young as 12 and women as old as 82.

Several years ago, Charlotte and I created some Nike ads that struck a nerve with a lot of people. Female people. Male people. Children as young as 12 and women as old as 82. We'd like to offer up a revision to the original, revised to speak to the numerals we feel measured by now, the road signs that tell us how far we’ve come, another year another year, like the marks a doomed prisoner makes on his cell walls. Isn’t that supposed to be a good thing, this being alive? Shouldn’t the more digits we add up give us some sort of prize, some sort of Yay Rah, you’ve gone past Go again, here’s a little reward? Isn’t living the point to this whole mad existence? But it’s not, you know it’s not, not here in Ever-Younger-Me-Me-Me-America. Why do we cringe or lie instead of accept and ask for more, please? Anti-aging. Anti-changing. Anti-living. We’re crazy, completely nuts if we think we can turn back time, break all the clocks. God, can’t we ever grow up.

And so, without further ado...the text should now read:

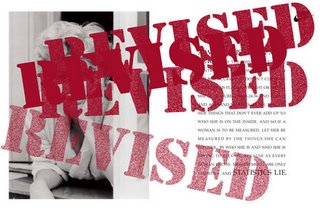

A WOMAN IS OFTEN MEASURED

BY THE THINGS SHE CAN’T CONTROL.

SHE IS MEASURED BY THE AGE OF HER SKIN AND HER FLESH,

WHAT FALLS TOO FAR OR HANGS TOO LOW,

BY THE DECADES SHE HAS SEEN INSTEAD OF

THE DECADES STILL TO GO.

SHE IS MEASURED BY NUMERALS AND MILE MARKERS,

BY 21 AND 39 AND 55,

BY QUANTITY NOT QUALITY,

BY ALL THE OUTSIDE THINGS THAT DON’T EVER ADD UP

TO WHO SHE IS ON THE INSIDE.

AND SO IF A WOMAN IS TO MEASURED,

LET HER BE MEASURED BY THE THINGS SHE CAN CONTROL,

BY WHO SHE IS AND WHO SHE IS STILL TRYING TO BECOME.

BECAUSE AS EVERY WOMAN KNOWS,

NUMBERS ARE ONLY STATISTICS.

AND STATISTICS LIE.